The nature, culture and living in a small village in Japan just after the last world war, reflected through the boy’s eyes.

Chapter17 Sports (1955~7)

Yoshiharu Otsuki (Sendai, Japan) and Yasufumi Otsuki (London, UK)

BACKGROUND MUSIC

Hubert Parry : 1st movement from Violin Sonata in d – minor

Fumi Otsuki : Piano Sonatina No.2 (The first theme is based on an English folk song, “In Bodmin Town”, and the 2nd theme is based on an Scottish folk song, “Loch Lomond”.)

Played by Fumi Otsuki (violin) and Sarah Kershaw (Pf)

30th Nov. 2022 St .Luke’s church in Sevenoaks, Kent

Boys generally like sports. The boy wasn’t good at sports (as mentioned in ‘ Japanese Rustic Life in the 1950s. 5.The sports festival at primary school’ [on Youtube]), but he did not dislike them. For example, he did judo for several years in his childhood, played baseball when he was a university student and tennis as an adult. However, he always enjoyed the physical side of sports – just exercising his body – more than exercising his brain by thinking of strategies to win.

1. Skiing

I am drenched in sweat; my finger tips and toes are numb with cold; the rucksack I’m carrying weighs heavily on my shoulders; I’m losing my balance and almost falling and it’s difficult to breath. I’m in the mountains skiing.

Physical activities were part of the curriculum for first-year students in my university. A student had to select one from many items such as tennis, table tennis, badminton, Japanese archery, field and track sports etc. and do it throughout the year. The university placed more emphasis on academic learning than physical education, which was barely enough to keep students fit and healthy. I was well aware of my athletic ability, or lack of it, and wanted to avoid the subject if possible. However, it was compulsory. I was thinking of choosing tennis, because it seemed like fun, and apparently many students had the same idea: the quota had already been filled by the time I got round to showing up at the application window. (The crown princess and the prince married in 1965. It was widely reported in the media that he and the crown princess became close playing tennis in Karuizawa (a famous resort), and a tennis boom subsequently spread throughout the country. It was three years later when I entered the university, and somehow, I wasn’t aware that tennis was still so popular.) I didn’t have a plan B, so just stood there vacantly. Then I noticed there was another application window for Japanese archery. And that’s how I became a member of the archery course.

Japanese archery (kyudo) is very different from Western-style archery, which is an Olympic event. In Japanese archery, an arrow of around 3 feet length (depends on the arm-length of the player) is fired from about 7.27 feet bow made of laminated wood and bamboo slats, with a 14.17 inches diameter target set at a distance of 30 yards. It is a long-established martial art practiced by about 140,000 people in Japan, with several distinct schools even now, although most participants use a combined style derived from all the schools. Beginners start by learning routine postures, and then progress to shooting arrows at a 20 inches diameter target about three feet away with bows of low tension. At first, even at this range, it’s difficult to hit the target, with arrows tamely dropping to the ground or flying off at impossible angles. After only a few attempts, novices develop muscle pain and have to take a break. It really isn’t as easy as it looks, and it takes a lot of boring practice to get the basic postures and actions right, and then to shoot arrows with increasingly stronger bows. These stronger bows are necessary because, in order to have a chance of hitting the target, the flight of the arrow has to be fast, and this can only be achieved with a strong bow. (Incidentally, I was never able to draw a competition bow to its full extent.)

When performed by a skilled bowman, the sequential steps of Japanese archery are not dissimilar to the Japanese tea ceremony, both entailing decisive movements and momentary pauses. After releasing the bowstring, the silence is broken by the sound of the arrow flying through the air, followed by the distant thud of it hitting the target, and then tranquility returns. It’s almost like a religious ceremony. However, I was totally bored by the monotonous practice long before I could reach such a lofty stage. The two hour lesson was way too long for me, and it wasn’t long before I started skipping the class. The university had already anticipated many students lacking the diligence to stick with it, and had prepared a ski tour for students to make up the credits.

Anyway, back to skiing. It takes about three hours by train and bus from the city of my university to the Zao hot spring ski resort. This village is located halfway up Mt. Zao, an active volcano -1840 meters above sea level, and people have been enjoying the curative waters there for about 1900 years. The water is highly acidic (sulphur containing aluminium-sulphate and chloride, with pH=1.6) and smells strongly of sulphate, which is said to make the skin smooth and be effective for treating dermatitis. The first ski slope was made in a field above the village in 1925 and then developed over time. Today, with 29 courses in 14 areas – all connected by lift and ropeway – it caters for skiers from all over Japan.

My university used to offer ski tours of 4 nights and 5 days more than five times a year to students and staff. The participants were divided into several groups according to their skill. Groups for beginners had systematic training with a PE teacher, while groups with more skillful members were free to ski as they wanted. As mentioned, the aim of this tour was to give students a chance to make up the time they’d lost skipping their chosen sports, in order to gain credits. Thus, the more time you needed to make up, the more of the tours you had to join, so I ended up going nearly five times.

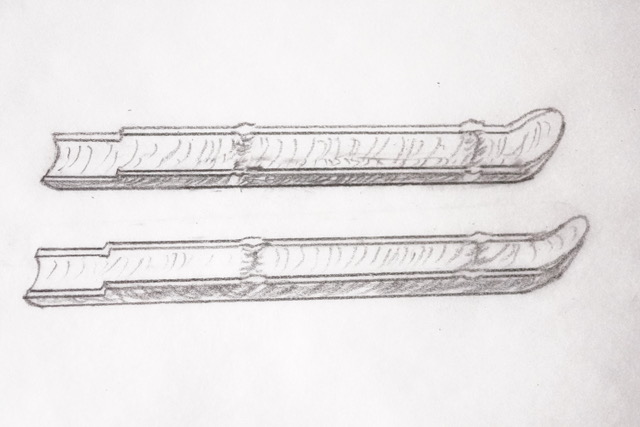

It didn’t snow much the first winter I went on the ski tours. There was no snow at the foot of the mountain, but there was enough for skiing on the slopes higher up. I was placed in the beginner’s group and started practicing on a gentle slope. When I was a child, I used to enjoy skiing on the slope near our village with homemade bamboo skis. As shown in the illustration, these were about 14 – 25 inches long and had a ridge at the rear to stop the heel of the boot moving, so that the skis could be controlled. However, due to the lack of a proper boot binding and the round bottom of the ski, it was very difficult to remain balanced.

Now, the boys were struggling to stay upright on the uneven slope, and they could not ski more than 10 or 20 yards before falling. They ended up feeling that skiing was a very difficult sport. Compared to the bamboo skis I’d used before, I found it quite easy to slide along with real skis. This was because the ski boots were firmly bound to the skis, the bottoms of the skis were flat, and the skis were long enough to make balancing easier. Furthermore, the ski poles could be used to steady one’s balance, so I smiled to myself as glided along. Unfortunately, I didn’t know how to stop, so I ended up falling anyway.

“See. It’s easy to ski straight, but now you must learn how to stop and turn. I‘m going to teach you how to do this, and you’ll be able to go home thinking skiing is fun,” the instructor said, expertly seizing on the opportunity provided by my fall.

“Can you see that narrow pass?” The eight members turned their eyes towards the direction the instructor had pointed. Looking up at the top of the mountain, a vast white slope could be seen stretching beyond the ski slope next to the hot spring town. Dotted among the deciduous trees lower down, there were a few conifers, which gradually increased in number further up the mountain. Eventually all the trees were conifers, and at the top, it could just be made out that there were white clumps.

“Can you all see it? All the trees at the top are covered with hoarfrost, though you can’t see that clearly because of the mist. They have formed clumps of ice of about two meters diameter and five meters height. As strong winter winds hit the trees, the water droplets in the air stick to the trees and freeze. This is repeated over and over again until the original tree shape is transformed into fantastic ice sculptures, which we call ice monsters. The ice monsters here are the most famous in the country.”

He went on, “You can see a place without the ice monsters under the gondola cable on the left and towards the top. This is the ski slope called Paradise Gelaende. There is a steep and narrow pass between the ice monsters from there to the top, which is called Zange (meaning ‘penitence’) Slope. This is one of several ski courses down Mount Zizou (the name of the mountain above the ski resort) to the place we are now. The reason why it is named Zange Slope is said to be because it is too steep to climb without submitting to the gods and asking for their help.”

“Do you all know Toni Sailer?” the instructor asked, ably playing the role of sightseeing guide. I recalled seeing the man in the news. At that time, if you mentioned Austria, Vienna would come to mind first, followed by the Vienna Boy Choir, and then Toni Sailer.

The instructor continued: “He is an Austrian skier who won the Triple Crown of alpine events – the first person to achieve it – in the 1956 Winter Olympics. He came to this resort the year before last year and skied from the top of the mountain to this spot in an incredible10 minutes.” I knew the name but the only thing that came to mind was him singing in a Japanese movie he had starred in, and I had absolutely no idea if 10 minutes was fast or not. The instructor could see we were not as impressed as we should have been, so he added: “Though we can’t see all of the route properly from here, it is particularly long, and even top skiers can’t ski it all at maximum speed. However, Sailer schussed down the whole course flat out.”

That they still hadn’t understood could be seen from their blank expressions.

“On the final day of the tour, we will go up to the top of the mountain and ski down to this point. It will take you newcomers all day to do it.”

Some people must have been regretting signing up for the tour. I remembered my experience of falling on a steep slope and trembled at the thought of it.

“Don’t worry – you’ll get the hang of it. Sure, Sailer skied straight down, but you’ll do it slowly with many turns. As I said, it will take you half a day to ski down, with all the turns and falls.” The experienced instructor expertly slipped in that part about falls, and it didn’t go unnoticed that he had also revised his estimate of how long it would take.

In the first lesson, we got used to the skis by walking with them on level ground and sliding down gentle slopes. Then we learned the basic way to slow down, that is, bending the knees slightly and bringing the skies together in front to make a V shape. This increases the pressure of the skis on the snow, which reduces speed.

This is called ‘bogen’, which is a contraction of the German ’pflugbogen’. It is thought that Theodor Edler von Lerch, a Major General in the Austro-Hungarian army, introduced skiing to Japan, so the terminology of skiing is German. Incidentally, pflugbogen is rendered as ‘snowplough turn’ in English, and ‘bogen’, as ‘edging’. (In Japan, words from foreign languages, like English, German, French etc., are feely used together without distinction.) Bending the knees more deeply increases the edging effect, and the breaking power becomes stronger.

Next, we tried putting our weight on one foot and edging on one ski, producing a change of direction. When you bend your knee and put your weight on your right knee, you turn left, and vice versa. This action was called ‘bogen’ as well, I think. In this class, the skiing techniques we learned were up to this level, and the objectives of the class could be achieved with only these techniques. Then we skied on various slopes, moving to a different one every half day. While getting used to skiing, we got a feel for the snow, learnt how to deal with incline changes and uneven ground, and enjoyed the beautiful scenery. When at last we could ski on all the different slopes with confidence, the aim of the class was accomplished.

Subsequent skiing tours would teach more difficult skills like turning with parallel skis (parallel christiania), continuous turns (wedeln), jumping over small hillocks, and sliding fast on steep slopes. At that time, the wooden skis were very heavy and long (I’m 5.53 feet tall and used 6.9 feet skis), and it took great power to control them. Women often fell because they were not powerful enough to control the inertial power of the skis. Recently, thanks to the development of industrial technologies, there are lighter and shorter skis made of plastic, which are much easier to master.

Anyway, thanks to four days of lessons, I acquired enough skill to ski down all the different slopes, falling only a few times per slope. And now it was the highlight of the tour: we would ski from the top of the mountain to the bottom. This event was originally planned for the morning of the final day, but the weather forecast said it would snow heavily on that day, so it was changed to the afternoon of the day before to avoid the chance of somebody getting lost on the slopes. We got to the terminal of the highest lift and were walking up the narrow course to the top of Mt. Zizou. We had to walk carrying the heavy skis on the side of the course while skiers whizzed down past us. Many snow monsters stood together on both sides. The snow was piled deep between them and anybody falling there would have had great difficulty getting out again. Everyone was walking slowly and carefully, panting while carrying their heavy skis on the slippery path, probably regretting having signed up for the tour.

After twenty minutes or so, we got to a small open space, where the leader gave us the order to stop. Getting my breath back, I realized it had stopped snowing and the wind had died down. I took off my goggles and looked around, astounded by the magnificent scenery. We were standing amongst the snow monsters in a white paradise under a clear blue sky. In the distance, I could see a panorama of snow-covered inclines down to dark coloured rice fields. The finely graduated colour changes of the view reminded me of an India-ink painting. Beyond this, the snow-covered tops of another mountain range sparkled brightly in the winter sunshine. At the top of a mountain in winter for the first time in my life, I was overwhelmed by the beauty.

I never really got much better at skiing, but I joined the university ski tours regularly to enjoy the beautiful scenery of the winter mountains. In the end, skiing became one of the few sports that I can actually say gives me pleasure, and the Alps remain a splendid spectacle that I hope I will be able to continue to enjoy in the future.

2. Harakiri

I had been teaching students as well as performing my own research in the university where I was working as an assistant professor. The direction of the research was of course based on the professor’s ideas. My professor was devoted to his duties with the university administration and academic societies, and to commissioning his staff to perform research activities. With the guidance of the professor, assistant professors selected research subjects, made a research plan and taught the students. (Of course, there was a tacit understanding between the professor and his staff that their activities should not extend beyond his professional field.) However, my research activities led in another direction and eventually I had to leave his area of study in order to develop my ideas.

At the end of the school year, we had to help the students complete their graduation thesis, which would then need to be revised in order to make a paper suitable to be read at a symposium. This process involved very close cooperation – more like living together as members of a family than the usual classroom relationship between student and teacher – and this sometimes led to problems. Occasionally, these differences of opinion, coupled with the basic incompatibility of a particular student and teacher, resulted in other members of staff having to take over. In order to prevent such problems, we took great pains to create a harmonious environment by having parties and playing sports together. My professor was fond of tennis, so I ended up managing tennis practices, matches and exhibition games with other laboratories. I, of course, knew little about tennis and had to pick up many things as I went along.

Every year the students were all very different people, but, strangely enough, I noticed that some personality traits seemed to be common to all of them.

Another school year started, but I felt that the new students were a little different to usual. They were a diverse group but all tended to be rather passive, which made me think we might have some problems with them.

All research initially depends on individuals and teams working independently. However, in my experience, productive research activities can be best achieved in an environment that encourages cooperation between staff and students. The inclination to work together in a group might be attributable to Japan originally being an agricultural society. Anyway, I had been worrying about how I could improve the harmony amongst the new students, when I happened to see a poster on a bulletin board for a ‘marine athletic meet’. I’d heard of it but had no idea what it was. Casually glancing through the information, I discovered that it was a rowing race open to anybody. The university boat club had been at the top of domestic amateur rowing, and had even competed in the men’s eight event in the 1960 Olympics held in Rome. It’s the only time that a Japanese university team has taken part in a rowing event at the Olympics. The university probably intended to commemorate this remarkable feat by holding the marine athletic meet. The sole event was to be the knuckle four*.

I had an idea: the teamwork necessary for rowing in races could be a good way to build a sense of unity among students and members of staff. Only five from our group of ten students would be needed to make a team initially, but if we won races and progressed in the tournament, there would be chances for other people to take part. I completed the registration and returned to the laboratory and told everyone we were going to form a rowing team and compete in the marine athletic meet. While the students seemed to be interested, the staff were not very keen, feeling there would be a lot of work involved. In the end, none of the other members of staff volunteered, so, being the one who’d suggested it, I had to join the team. The meet was to be held at a canal about six miles east of the city the university was located in. (This area was devastated by the huge earthquake and tsunami of March, 2011.) Before the actual event, we would have the chance to take one lesson from the crew of the university boat club.

So, we went to the canal to learn about rowing and the boat race, and the members of the club boat crew gave us helpful instruction. For example, we learned that the boat can move unexpectedly fast when the four members of the crew row in unison. However, each crew member has a different physique, different muscular strength and sense of timing, and cannot row together without a coxswain to coordinate their efforts. Even then, they can fall out of rhythm, and one rower being late in removing his oar from the water between pulls can result in considerable drag. Sometimes, a lack of coordination can even result in a crew member being hit be an oar and getting knocked overboard. After listening to the wise words of our instructors, it was time to have a go ourselves, so we got into a boat and tried to row following a coxswain’s commands. Pulling the heavy oars through the water was so hard that we instantly broke into a sweat. All of us had a try and by the end of the practice we were just about able to move the boat forward. The actual race would require a much higher level of skill because there would be two boats racing side by side, and the canal was not particularly wide.

The first round: At the sound of the starting pistol, the two boats started to move forward. All the members of our crew were rowing in unison in accordance with the coxswain’s commands, but after a short time the other boat started to pull ahead. Noticing this, our crew lost their composure and their rowing became uncoordinated, and then we fell even further behind. The coxswain of our boat shouted, “Don’t watch the other boat – pay attention to my commands!” However, a quick look at the wild way our oars were moving showed that nobody was heeding his words, and the gap between the two boats widened. He now ordered individuals by name, “Sato! Takahashi! Fall in with the person in front of you.” Being inferior in strength to the other two members, even if they slowed somewhat in order to match the rhythm of the two stronger rowers, it wouldn’t result in the boat slowing down. “Ueda! Tanaka!” he shouted, “We’re relying on you. Increase your strokes a little to my count.” The coxswain was doing a fine job: as soon as he noticed that the crew were not responding together to his instructions, he immediately addressed them by their names and directed them individually. After a few minutes, our team caught up and eventually passed the finishing line with a small lead. I was curious about how the coxswain had gained his skill, so I asked him about it after the race. He said that even though it was in a different sport, he was an athlete himself, and he had realised through experience the importance of teamwork. His positioning of the rowers – strong/weaker/strong/weaker – was also surprisingly effective. Through experience, everything is understandable.

The second round: The successful coxswain was again to direct our crew, but this time the first four rowers would be rested and replaced by another four from our team. Everyone was excited and the team seemed to be galvanised by our victory, so my original purpose for competing in the event was already being achieved. Following our winning strategy from the first race, the strongest rower sat in the ‘stroke’ position (just in front of the coxswain), and the other rowers would fall in with him. This time, I was part of the crew and sat in the bow position (the seat furthest away from the coxswain). We all fully understood the importance of following the coxswain’s commands exactly and ignoring the other boat. At the sound of the starting gun, we set to rowing, and I immediately felt we were getting more power than in the practice. I pulled the oar with all my strength in complete unison with the rower in front of me, all the time fighting the urge to cast a sideways glance at the other boat. Sweat filled my eyes, my arms were losing power, and I was getting cramp in my legs. Then suddenly, the rower in front of me was slowing down, so I quickly matched his strokes, and then I realised we had passed the finishing line.

“Who won?” I asked. It turned out that we had won by some distance. As we sat there breathing heavily and wiping off the sweat, the club boat crew who’d trained us came up to us and said, “That was the best time of all the teams so far. If you can keep this up, you’re going to get to the final and win!”

The third round: Almost all the sports clubs our students belonged to were weaker than the ones in other universities, but they experienced victories as well as defeats. They sometimes seemed unmoved by the results, good or bad, but they got excited about contests that had been won after a hard fight, and this seemed to build a sense of unity among them. I think this is what had happened in our case too, so in a spirit solidarity, they asked me and another member of staff to be part of the crew for the next race. The coxswain would be same, of course, and then students would occupy the bow and stroke positions, with me and the other member of staff between them.

The starting gun was fired. The coxswain, completely at home now in his role, calmly issued commands, and we made a smooth start. Seeing that we were properly coordinated, he gradually increased the speed of his count. I tried not to look but it became apparent that we were ahead of the other boat, and judging by the area of bank, we were not far from the finish. Then suddenly we stopped. Between pulls, my colleague’s oar had clipped the top of a ripple, causing his oar to get caught in the water, and the momentum of the boat rammed the oar hard against his belly. We had learnt about the possibility of an accident like this, but we had no idea what to do to get out of trouble. The coxswain shouted, “Mr. Abe! Push down hard on the oar and get it out of the water.” While he was struggling to do it, we rowed with all our power, but the oars were heavy and it was difficult to get moving again. By the time we had recovered, the other boat had overtaken us and went on to cross the finishing line.

While Mr. Abe was apologising to everybody, the students, in spite of the defeat, were cheerfully preparing to pack up and leave. I remembered that I hadn’t minded too much when I lost judo matches as a child, so the intense disappointment I felt this time was rather surprising.

The club boat crew commiserated with us: “That was really a pity. When an oar hits a rower like that, it’s almost impossible to recover from in a tight race. We call it harakiri!”

The knuckle four format – four rowers in a standard boat with a coxswain – was established by the Japan Boat Association with the aim of increasing the popularity of amateur rowing in Japan, and accordingly is only an event in domestic competitions. The boat is 11.67 yards long and 2.84 feet wide, with two oars on each side and four seats that can slide backwards and forwards. Four supports for the oars are attached at right angles to the gunwale. The rowers move the oars backwards and forwards by a combination of bending and stretching actions. In more detail, while the oar is held in the air, the rower stretches out his arms and bends his knees and back, which moves the seat forwards. At the furthest extent, the end of the oar is dipped into the water. Next, the rower pulls the oar through the water, which straightens the legs and back and folds the arms, causing the seat to move backwards. The boat is propelled forwards by repeating these two actions. The coxswain sits in the rearmost seat, and is responsible for steering and setting the pace for the rowers, which is dictated during the race by taking into consideration things such as the conditions of their lane, position in relation to other boats, the degree of exhaustion of the rowers etc. The coxswain also plans strategy before a race, and has to decide quickly and calmly how to respond when something unforeseen (like a ‘harakiri’ incident) happens. His role, therefore, is crucial. (This is also true of rowing eights. )

The end

<<<Showing again the stories presented in Youtube>>>

1. Beginner’s luck (1955)

The boy’s line of vision travelled gradually from the tatami mat to the faces of the spectators, and above them to the wall of the gymnasium and the lights on the ceiling. Then he fell heavily. He was aware of the sound of his body hitting the mat, mixed in with the loud laughs and cries of encouragement from the spectators. He lay on his stomach and half-turned to see another boy lying on his back.

“Stand up,” a deep voice ordered. The two boys stood up and another command was given, “Start.” It was a judo match – a knockout competition being held for members of the judo club at the high school gymnasium as part of the sports festival in his town.

A week before, his mother had taken him to the dojo to join the judo club, because she was worried about him not having any friends, having just moved to the town. What had he learnt in such a short time? Well, how to put on the uniform, bow to an opponent, break one’s fall (How to roll over safely when thrown down), and kumite (The way to grip an opponent’s uniform. There is only one basic rule: the left hand holds the opponent’s right sleeve and the right hand holds the left collar – that’s all.) Of course, there was no time for him learn any moves or throws, so it was ridiculous to let him fight a match with only these skills. If something like that happened nowadays, people would think it irresponsible, but at that time nobody thought it was unreasonable.

He was fighting against a boy of his own age who had joined the dojo before him. He was holding his opponent’s uniform as he’d been taught but had no idea how to fight. (There were no sports facilities for things like judo and sumo in the village he used to live; children usually amused themselves by fishing or wandering in the forest) He had no idea what to do with his arms besides holding his opponent’s uniform, so he decided to try and use his legs, aiming a kick at one of his opponent’s legs. Of course, his opponent easily read his intention and pulled back his leg. Then he used his weight to pull his opponent towards him and swung his left leg but missed again. Though his plan of attack required him to use both legs, he was so clumsy that he could only use his left leg. His opponent was also aware of this and took evasive action. He swung his leg again, this time making contact but too weak to fell his opponent. He did this over and over, like a cat swinging its forefoot trying to hit a toy being dangled temptingly by its owner.

Jab, jab, jab, cat punch.

Jab, jab, jab, cat punch.

Jab, jab, jab, cat punch

He tried to think of another way to defeat his opponent but his sole week of practice hadn’t given him any ideas. He landed more cat punches but too weak to trouble his opponent. When he did try to land a stronger punch, he fell, and that’s when he found himself on his stomach on the tatami. He heard the spectators laughing; they had enjoyed his ineffective cat punches and the resulting fall. The adversaries stood up again and performed a kumite. Being laughed at like that made him feel like giving up, but he continued swinging his leg.

Jab, jab, jab, cat punch.

Jab, jab, jab, cat punch.

Jab, jab, jab, cat punch.

And then suddenly, somehow his opponent had fallen on his bottom.

“A half point,” the referee’s declaration echoed in the hall and the spectators gave him a big round of applause. The players stood up and restarted. The boy had no choice but to persist with his style of play:

Cat punch – miss – jab – miss – hit – cat punch.

The spectators were getting excited. And then, by some whim of the gods, his cat punch kick connected with his opponent’s leg and knocked him down again.

The referee raised his hand and declared, “A half point and sum up to ippon,” and the boy got another big hand from the spectators. He was doing the fighting sport for the first time in his life and had won but, being completely out of breath, could not savour the moment. Furthermore, in accordance with the rules of the tournament, he had to prepare himself to face the next opponent.

The next opponent had a strong physique and much more experience. He held the boy so tight that his weak kicks could not reach, but he still had no other idea than to repeat his previous line of attack. He seemed only to be swinging his leg, which caused the spectators great amusement. His opponent used a judo waza (technique) against him, and yet somehow he managed to stay on his feet. His cat punch occasionally hit his opponent’s leg but without any effect.

Then the gong rang. The referee separated them saying, “Stop fighting,” and declared the bout a draw. He was entirely worn out and had lost all feeling in his left leg. As usual, nobody from his family had shown up to offer encouragement, but his mother heard the news and had one of her pupils bring him a peanut-butter roll for lunch as a reward. The taste has never been forgotten.

2. Will-power(1956)

“Seoinage!” (seoinage: a judo manoeuvre )

“He’s pushing you – uchimata!” (uchimata: another technique)

His team members were giving him enthusiastic vocal support.

It was the inter-school judo competition for junior high schools in his district, and now he was fighting on the mat with an opponent. It looked like he was holding on to his opponent’s uniform and aggressively pushing and pulling, but actually it was the boy who was being shoved around by his powerful opponent. His first win in judo with the cat punch kick had decided that his forte would be foot techniques, though there was little difference between the kosotgari (hooking the outside of an opponent’s ankle) that he had used in his first bout, and the kouchigari(hooking the inside of an opponent’s ankle) that he was trying to employ now.

Now he was aiming at a chance to execute koutigari. Basically, this technique involves pushing an opponent over by hooking the inside of his ankle when he is leaning backwards and off balance. The boy intensified the hooking power of the technique by grasping the lower part of his opponent’s judo pants and pulling.

In judo, it is usually difficult to bring down an opponent standing in a posture of balanced readiness with muscles relaxed. The aim, then, is to try to make an opponent lose balance by pushing or pulling. For example, when an opponent is putting his weight on his front foot to push strongly, you can throw down him using manoeuvres like seoinage and uchimata. When he is pulling you, you can throw him down him with foot techniques like kouchigari. Of course, besides techniques involving forward or backward movement, there are also manoeuvres for movements to the left or right.

The stronger the pushing or pulling power is, the more effective the manoeuvre becomes, but sometimes it can bring about an untended result. When you push your opponent too hard, you are in danger of falling victim to tomoenage. With this technique, you abruptly turn your back to your opponent and throw him over your head by pulling his tunic with your hands at the same time as pushing against his belly with your foot. When this daring attack is successful, it looks spectacular, so this technique is favoured by many judoists. However, having to hit exactly the right place on the belly makes this technique difficult. Hitting the belly or chest is the aim but sometimes in error a player is struck in the groin. This, of course, causes agony, so it’s hard to understand why spectators often respond to this injury by laughing. Men laugh in sympathy but women are also sometimes amused, which adds embarrassment to the acute pain. This combination makes most judoists wary of falling victim to the mis-executed technique. Consequently, they lack commitment, which leads to missing openings for attack when they occur. Seeing this timidity, teammates offer cries of encouragement, while spectators respond with disapproving shouts and booing. The judoists, thus, have to perform under this extra pressure.

In sumo wrestling, when a bout leads to an extended deadlock, the referee urges the players to be more aggressive, saying ‘Hakkeyoi’. And recently in judo, the referee gives a minus point to players that are too passive. When the boy used to do judo, it had simply ippon (win), and wazaari (a half point), so many matches used to end in a tie.

3. The three crows(1957)

Grasping the collar of each other’s judo jacket, the boy and his opponent were pulling each other trying to gain an advantage. It had been more than two years since he had joined the judo club, and this was a first dan promotion match. He had learnt several techniques and taken part in matches, and had even acquired the round shoulders and bandy legs of a typical judoist. The promotion would be left to the judgement of the head of the dojo, but it was generally thought that two wins in promotion matches would be enough to secure the advancement.

We have an idiom in Japanese – ‘three crows’, which means the 3 most important people in a particular situation. This is said to be because the crow is a very wise bird. Sometimes it can also mean ‘the 3 best vassals.

This dojo also had its own ‘three crows’ among its ranks. They were well-known in the area as strong young judo wrestlers. One of them was even invited to enter a private university in Tokyo in order to be a prospective participant in the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games. Three 12-13 year-old boys were the current new generation of the three crows. The best among them was a boy called Isamu. He was relatively tall and muscular for a 12-year-old. He was quick and his seoinage was especially skillful. Next was Tsuyoshi. He was one year older than the other boys and had a big, tough body built up from farm work. He usually threw his opponent by brute force, using powerful techniques like uchimata and haraigoshi. The third one was the boy. He was not tall for his age and had a slight body, so his judo skills were behind the others. On the other hand, his supple body gave him an advantage with foot techniques like koutigari and osotogari. He usually bore up against his opponent’s power, and looked for the chance to execute his trump card attack. This style could solely be attributed to his first experience, when he had won with the foot technique. His second secret was the additional training he was given by the elder three crows of his dojo. When they were in junior high school, they were taught by his mother. While teachers at that time (and today, maybe) generally tended to show partiality towards academically high achieving pupils, she did her best to treat all her students fairly. (She was, however, particularly strict with her son, always insisting he get good grades.) The 3 students did not have good grades (which the boy was well aware of because he often helped his mother to mark examinations), but they clearly felt that the boy’s mother did not treat them less favourably. Accordingly, they looked kindly on the boy.

He was usually the weakest among the junior three crows in practice. He always made an excuse for it to himself, saying that because he was the last of the 3 to join the dojo, it was natural that they should beat him. Still, he did not want to lose against Isamu, who was not only a very good judoka, but also a good student – an all-rounder. The boy, on the other hand, didn’t excel at either. The two boys got on well together but, feeling inferior to Isamu, the boy was sometimes hostile towards him. This led to the boy quite often recording unexpected victories over the older boy in official matches like promotion tests.

In a promotion test, a player would usually qualify for promotion to shodan (the first grade of the senior class, distinguished by the right to wear a black belt) with two wins. In that day’s, there were three bouts involving the candidates, and two had already finished. The first match was between the boy and Tsuyoshi, in which the boy was toppled by Tsuyoshi’s powerful taiotoshi and held down on the mat (osaekomi). In the second match, Isamu won against Tsuyoshi with a sharp seoinage. And now, the boy was fighting with Isamu in the last match. They were holding each other tightly as they grappled, Isamu standing upright and the boy with his back bent adopting a low posture. To all watching, Isamu was clearly the favourite to win.

Trying to lift the boy’s body to unbalance him, Isamu looked for an opening for his seoinage. Each time, the boy evaded his attack by sweeping Isamu’s legs and ducking into the space under Isamu’s arms. However, the boy could not muster any attack against Isamu due to his greater physical strength. Isamu pushed, pulled and swung his opponent from left or right, continually looking for a chance to employ his seoinage. He had many strong techniques besides seoinage, but for some reason he was only trying to attack with the one manoeuvre in this match. Maybe he wanted to celebrate his promotion with his signature technique, as he would secure shodan if he won the match. The boy was waiting for the chance to put into action his secret plan of attack.

The boy’s idea was: If Isamu could not break down his opponent’s posture with his usual approach, he might risk bending himself backwards to lift his arms high, which would move his centre of balance backwards. At that moment, the boy would lower his upper body and push Isamu’s body, while pulling on Isamu’s right leg using his heel and holding on to his judo pants with his right arm(koutigari). That was his one chance to win the match.

Time was running out. If the match ended in a draw, Isamu would get one win with one tie and the boy one loss with one tie. Of course, he would have no chance of promotion. Isamu was in a difficult position. The head of the dojo had a high opinion of Isamu and wanted to give him the promotion by two wins, and Isamu was smart enough to know this. Therefore, he shouldn’t be having any problems with a weaker opponent. This pressure resulted in his uncharacteristically stiff movement and a loss of his usual speed. With time running out, the boy could sense Isamu was getting impatient.

It was unusual for Isamu to push an opponent strongly with both his arms at the same time, and the boy could easily predict Isamu’s next action. Isamu must be planning to unbalance the boy by using the boy’s reaction to his pushing to lift him up and execute a seoinage. Watching Isamu’s feet, the boy pushed upwards, causing Isamu to shift his weight from his toe to heel. It was the moment to attack. He had used it in practice with seniors many times to win matches, and nobody had been able to defend against it. He entwined the heel of Isamu’s foot with his right sole and unbalanced Isamu by lifting his body, then pulled with his right leg and right hand, which was tightly grasping Isamu’s pants. Isamu fell down spectacularly.

“Ippon”

The head of the dojo lifted his right hand diagonally and loudly declared his judgement without hesitation, and without trace of the disappointment he must have felt. Consequently, each of the young three crows finished with one win and one loss, and no-one would be promoted to shodan.

The boy fought aggressively against Isamu, but was usually much more weak-hearted with other opponents. Whenever his turn to fight approached, he often had to run to the lavatory. Then, feeling ashamed, he tried to make excuses to himself for his timidness: ’What do people have to fight for? It is not necessary to fight in a time of peace. When people build up their fighting spirit through sports, they become emboldened to start wars, just like the last world war. I wish the world peace, so I don’t need to learn judo.’ In the end, he gave up judo and started to play clarinet in the brass band. As his reason for quitting could basically be attributed to his laziness, it could be expected that he wouldn’t last long with the clarinet either, and this proved to be the case. (He actually stopped playing clarinet in high school, and oboe after only a short time at university.)

Isamu did later get a black belt, but he was always more of a thinker than an athlete, eventually becoming an engineer, apparently.

4. Appendix (Brass band)(1957)

The boy’s junior high school held a sports festival annually. The aim was originally to provide some variation in the school curriculum, and then it came to be seen as a way to give students the opportunity to enhance their physical fitness, and also to raise the profile of the teachers’ activities for the parents of the students. Teachers ended up having to do all sorts of jobs, which no doubt still happens all over the country. In this school, however, they had a big problem. They’d had a sports festival at the boy’s primary school, which was a day-long event enjoyed by most people from the village. The problem at his junior high was that although the morning sessions were well-attended, there were hardly any spectators for the afternoon sessions. Every year, the teachers tried to come up with ways to make the afternoons more popular but without success. When a new headmaster arrived at the school, he demanded that they made the afternoon session more entertaining. After many futile meetings, one teacher suggested an alternative reason for the lack of spectators: ‘We’re always talking about ways we can improve the afternoon programme, but I don’t think that’s the problem. There’s an hour after the morning session when there’s nothing to do but wait around for the games to restart, so people go home. If we could find something to keep people amused, they would stay for the afternoon session.’ That seemed a reasonable explanation but nobody had any idea how to fill the time.

Continuing the events without a break might solve the problem, but it would be hard for the competing students and the teachers running things. The teachers were particularly worried about this and were not very keen on filling the break with another activity that they would have to take charge of. At that moment, a teacher spoke up, “How about livening up the lunch time break with the brass band? We don’t have much opportunity to listen to music in this town, so we might even get extra people coming along for the music, besides holding on to the morning people.”

As only a music teacher would need to sacrifice his lunch break, this suggestion quickly gained approval among the teachers. Additionally, the teachers were sure that the brass band members were generally not good at sports, so very few would be involved in the games. They finally came up with the idea of having a marching band, with which the head master was completely satisfied.

The brass band members were practicing marching in the schoolyard.

Please allow me to digress for a moment. In the junior high school, students could choose between sports or cultural studies for extracurricular activities. As they had no judo team in the junior high, the boy joined the science club. However, there were no senior members and only two newcomers, including him. They had no idea what they should really be doing, but everyday after school they went to the science laboratory and spent several hours observing the cross sections of plants and vegetables cut by microtome. While they were making sketches of an onion, the door opened and the science teacher came in. “Recently, I noticed the readings on some of the instruments had changed. Now I can see that you’ve been in here touching them without permission. If you want to use the instruments, ask me first,” he scolded them angrily.

He was the person responsible for the science club being approved by the school and could have been expected to give newcomers some instruction at the beginning of the term, instead of which he just scolded the boys. They were just playing at being scientists, without any idea of method or reason. This could hardly be called education. The teacher was well known for being unfriendly, and the telling-off just confirmed it. However, after a few minutes, he calmed down and took a metallic object out of the closet. He put it on the table and said, “You probably haven’t seen one of these before but it’s a model engine – attach it to a model plane and you can fly it.”

“Have a look at these,” he said pointing above him, “I’ll start one of the engines for you.” The boys stood open-mouthed when they saw the hitherto unnoticed model planes suspended from the ceiling. There were wooden models of fighter planes with a wingspan of about 1.5 feet. “Wow! A Zero-fighter. Cool!” The boy’s friend exclaimed in admiration.

“Yes. That’s right. The Zero fighter was the best of our old army airplanes. I flew in one once – fantastic manoeuvrability – my head was spinning. This model took me six months to make, but I’m reluctant to fly it because landing is so difficult that

it almost always causes a lot of damage. (At that time, there was no radio control, so model planes were controlled by an attached wire, which made a safe landing very difficult.) Until I make another one, I just want to exhibit it like this.”

He skillfully prepared to start the engine, clearly in a much better mood now.

“Watch. When I rotate the propeller, the engine will start.”

He gave the propeller a good tweak, and the engine started to rotate the propeller. A puff of smoke appeared with a loud bang, which caused the boys to take a step backwards. Stopping it abruptly, the noise still ringing in their ears, the teacher urged, “Why don’t you try it? Just put two or three fingers on it like this and rotate it strongly anticlockwise. It won’t start unless you do it firmly, and be careful to pull your hand back as soon as the engine starts, otherwise you’ll get your fingers caught in the propeller.” The boy tried to follow his teacher’s instructions, but the propeller was much stiffer than he’d expected.

“Come on. Put more effort into it!” the teacher encouraged him. He tried to give it a stronger turn, but the teacher’s warning about the possibility of the propeller hitting the fingers weighed on his mind, making him draw back his fingers before the rotation was complete.

“Give it a real tweak. Don’t be such a wimp!” his teacher urged. He felt embarrassed but tried to start the engine again. After several attempts he did it, but the embarrassment he felt being called a wimp by his teacher took away any sense of accomplishment. His friend, however, was able to do it first time.

“You are both approved as members of the science club. You have permission to do experiments with chemicals and use equipment as you like.” So saying, the teacher stopped the engine and immediately lost interest in the boys and left.

Thereafter, the teacher never appeared again, and the boys were free to use the optical microscope to observe the cell structure in plants in the science laboratory every day. They gradually developed subjects for observation as the interest took them but soon came up against the limits of their undirected investigations. Eventually they got bored and started playing together at home instead, and although that was the end of the science club, the boys became lifelong friends. After that, the boy bought a model engine and enjoyed flying his own model airplanes. Furthermore, that short period of activity seemed to influence their choice of profession, as the friend became an engineer in the agricultural machinery industry, and the boy went on to work in the field of electronic materials. So it seems that their short experience in the science club had lifelong effects.

After the breakup of the science club, the boy’s mother insisted that he join another club. The problem was which to choose: sports clubs were out because of his lack of athletic ability; the drama club would be no place for such a shy individual; intellectual activities like English conversation were not suitable for somebody who didn’t like studying.

“You like listening to music – why don’t you join the brass band? The music teacher in charge of the brass band is very kind, so I will ask him about you.”

She decided this without any consultation with the boy. He routinely turned down her suggestions, even if they were things he wanted to do. But this time, liking music so much, he accepted it instantly. Several days later he went to the clubroom, where the music teacher handed a clarinet to him saying that he and the boy’s mother had decided it would be the perfect instrument for him. As it was another of his mother’s decisions, he only accepted it reluctantly but soon got interested in how to play it. A senior member taught him basic things like how to hold it, finger the keys, where to place his lips on the mouthpiece and how to blow etc. It was all very interesting for the boy, so he tried not to be hurt when the teacher said, “To be honest, I wanted to have somebody play tuba or saxophone, but they would be too heavy for you to handle easily, so I chose clarinet.”

After three days, he could play the easy marches. He continued to make progress and after a month he was given the role of second clarinet. However, all he was doing was putting his fingers on the appropriate keys without any understanding of the music, and as all the marches were in double time, his knowledge of rhythm was fundamental at best. In breaks from practicing, the music teacher sometimes shared his knowledge about music with the band members. They enjoyed his talk about episodes from the lives of composers and various things about classical music and instruments, so it was unfortunate that he had to resign due to ill health. (His mother told him that he had lost half of his lung capacity after contracting tuberculosis before the war, so this second occurrence was very serious.)

Then somewhat unexpectedly, the science teacher mentioned earlier took over the position. It is not unusual for people with scientific backgrounds to like music, but he knew nothing about it. The music teacher taught him the basics about conducting, but the science teacher had no feeling for music and swung his baton in a monotonous one-two, one-two movement during the marches.

Anyway, he agreed to take on the job of filling the lunch break interval of the sports festival with the marching band performance.

They were practicing marching under a blazing sun. Several sections were trying to march along the white lines painted on the ground while playing their instruments, and they were making a real mess of it. When they concentrated on walking straight, they completely lost the rhythm of the music, and being out of step, they bumped into each other. The teacher got one student to conduct while he sat in the shade and angrily shouted orders through a megaphone:

“Trombone, stay on the line.”

“Trumpet, I can’t hear you.”

“Drum, you’re out of time.”

He didn’t seem to notice that all the instruments were playing out of tune with each other. When they were exhausted after so much fruitless repetition, the teacher finally called for a break, which was due to him being tired of shouting rather than any concern for the boy’s well-being. When they had all gathered in the shade, the teacher went up to the boy and said, “Your marching posture is awful. Your back is bent and you walk in a really strange way – you look like a sumo wrestler. If you can’t do better, you won’t be able to be in the marching band.” There were a few unsympathetic laughs and the boy’s face reddened.

He took what the teacher had said to heart but couldn’t think what to do about it. In judo practice, he was leaning against a wall, lost in thought. They were practicing looking for attack openings by pushing and pulling each other. Watching the others, something occurred to him: “That’s why sumo wrestlers adopt that stooped posture. Judo players are always bending their backs to observe the movement of an opponent’s body in order to attack and defend. And they walk with their knees bent to defend themselves from an opponent’s foot techniques. I wonder what would happen if I reversed the styles.”

He tried judo standing straight and without bending his knees. His partner brought him down in a moment. He then tried both approaches with marching. However, although he’d only been training for two years, the judoist’s bent posture was difficult to change. Furthermore, whenever he concentrated on playing his instrument, he naturally stooped and walked bowlegged. Conversely, when he paid attention to his posture, he made mistakes with the fingering and fell out of time. The sports festival was approaching. What should he do? If he could not solve the problem quickly, he would be kicked out of the marching band. He worried about it deeply. Finally, he decided that judo and the marching band were incompatible, and that he would have to choose one of them. Just at that time, his family bought a stereo system and several records. He immediately fell in love with listening to classical music, gave up judo and was able to play with the marching band in the sports festival. After that, he was never again very enthusiastic about sport.

The end