The nature, culture and living in a small village in Japan just after the last world war, reflected through the boy’s eyes.

Chapter16

Misunderstanding (1953~8)

Yoshiharu Otsuki (Sendai, Japan) and Yasufumi Otsuki (London, UK)

1. Sequel to ‘A natural misunderstanding’

‘You walk through a beautiful field of flowers and arrive at a wide river. You ride a ferry boat there and cross the river. Then you arrive in the world of death at the moment you reach the other side. (Or there again, some people say that death occurs the moment you step on the boat.) In Japan, this is said to be a typical story told by a person who has had a near-death experience. Having completed the journey, you will be brought before Yama, the King of Hell. He knows about all your deeds during your lifetime, and he weighs them up before deciding whether you will go to heaven or hell. This part of story may be based on folklore attached to Buddhist stories imported from India through China, and is widely believed in Japan. Of course, while somebody who has had a near-death experience is able to relate what happened to them, the dead tell no tales. The experience of ‘passing through a flower garden and arriving at a riverside’ is not uncommon and there are several variations, but all of them describe a feeling of peace and being at ease while traversing the garden.

Of course, this is said to be unscientific and mere superstition. (I have heard that one possible origin of the story is from a book written in China in the seventh century by a Buddhist priest. Apparently, he tried to wake up people in their last moments of life and asked what they had been dreaming. Many of them described similar images to the above-mentioned story. However, I cannot find this book now, so I’m beginning to doubt my memory.) Recently, similar stories have been a popular topic for discussion in western countries. There are many studies and explanations about the mental process involved in death. One plausible explanation about near-death experiences is that, as death is the most feared part of our existence, this kind of story is already programmed into the brain and kicks in when somebody is close to death.

As a human being piles up a mountain of unsettling misunderstandings in the course of a lifetime, surely it is a comforting to think that this natural mechanism brings peace at the end of life.

2. Dèjá-vu (1972)

This is an experience I had when I was a university student. I had been drinking heavily with my friend at his apartment and fell asleep there. I woke up in the dead of night feeling uneasy. Even though I had never been to the apartment before that night, it felt strangely familiar. Trying to ignore the terrible headache that was gradually intensifying, I looked around the room and tried to work out why it felt like I’d been there before. Everything made me feel uncomfortable – the dirty walls, worn wooden posts, torn paper sliding doors, and all the furniture, and yet I’d seen it all before, somewhere. I racked my brains but could not pinpoint the occasion, but it was known to me, all the same. Tossing things over in my muddled mind, an image came to me. I was sitting on tatami mats, and wearing kimono. I could smell incense. It somehow felt like a scene from a book or movie set one hundred years ago. Since I’d only been born twenty years earlier, I later speculated that it might have been a memory from an earlier life.

(Early Buddhist texts talk about the transmigration of the soul, as in Hinduism. That is, the soul is reborn in many different creatures, and sometimes lives again as a man. Actually, new denominations of Japanese Buddhism don’t refer to the never-ending cycle of reincarnation, and people are just told that they will go straight to heaven or hell after just one death. However, although most Japanese have no deep knowledge of Buddhism, many may still have an idea of the ‘transmigration of the soul’ buried in their subconscious mind. I believe this accounts for what I took to be Dèjá-vu. I have experienced this feeling to varying degrees but basically don’t believe in the supernatural, and I certainly don’t have any special powers. Consequently, I concluded that the experience described above was not really Dèjá-vu. However, the following story I do believe to be an example of this phenomena.

One evening when I was 26 years old, I visited the family of my fiancée for the first time. I spoke briefly with her parents and then went to her room. Neither of us were very talkative and we were still shy with one another, so being alone like that was uncomfortable for us. We started looking at some family photos together as a way to break the ice. However, I didn’t know anybody in the photos and soon became bored. I didn’t want to offend my fiancé so I stifled my yawns and feigned interest as we turned the pages. While looking at photos from her girlhood, one photo attracted me. There were three girls wearing beautiful Kimonos. It might have been taken on New Year’s Day or Girl’s Day (March 3rd), or some other festival day. Do you remember my description in 1. Photograph(1953) in Youtube version?. It was the same photo. It somehow seemed to say that we had been promised for each other from that time. It’s certainly not a dramatic example, but I like to believe that it certainly was Dèjá-vu.

3. Swallowing my pride & confessing my small-mindedness

The students in the graduate school of science usually present their study reports at domestic or international colloquiums several times a year. In the autumn of 1968, a domestic colloquium of my field was held in Hiroshima. I’m sure readers know that this city suffered a US atomic bomb attack at the end of the last world war. I arrived there on the day before the meeting and visited the Atomic Bomb Memorial Museum in the afternoon. I was looking around the exhibits in the quiet hall with a few other visitors when I had the feeling that somebody was watching me. I turned around and on the other side of the hall, there was an elegant middle-aged lady who appeared to be looking at me. She immediately turned her head away. I continued around the exhibits but couldn’t stop thinking about her and the strange expression she’d had on her face. Then it occurred to me that because I have a small keloid on my face, she might have inferred that I was a victim of the bombing. I felt embarrassed and hurried away.

I went back to my hotel and after a while I calmed down and tried to work out why the experience had upset me.

Just after the last world war, it was often a news headline that atomic bombing casualties were discriminated against by people in the western part of Japan, including the Hiroshima area. In my area, the north, I had never heard of such a thing. I had nothing but sympathy for them, so that wasn’t why the woman’s misunderstanding had troubled me. I realised that the reason was that it had reminded about being teased about the keloid by the boys in my neighbourhood when I was a child, to the extent that I developed an inferiority complex as a result.

Looking back on it now, I feel I should have controlled my feelings and shouldn’t have left. I should have tried to talk to her and find out the reason for her expression. If my guess had proved to be right, I should have corrected her misunderstand-ing. Then we could have had a talk about how the bombing was unjustified and shared our sympathy for its victims. After that, our discussion might have progressed to how we could eliminate these terrible weapons from the world , or what could be done to support the survivors of the bombing. What a valuable exchange it might have been. However, to my great shame, I was defeated by my trauma and ran away.

4. Mr. Yamanaka

I am sorry about the serious nature of the last story and would like to finish this chapter on a lighter note.

I was seeing a visitor in the reception room of my company. Feeling the conversation was a little awkward, I fiddled with his business card.

Earlier that day, I’d had a telephone call from the boss of a business division – “Somebody is coming to see me next week, but unfortunately I have an important business meeting at that time. Could you see him on my behalf, please? Apparently, he has some business proposal.” We got on well together, so I readily agreed. And so here I was with the visitor.

“How do you do. My name is Takeshi Yamanaka. I took part in the Melbourne Olympics – Do you know my name?” As well as his name, I instantly remembered many things about those Olympic games 40 years before. “Of course, I’ll never forget your name, Mr. Yamanaka – Nice to meet you.” Being flustered, I messed up my formal greeting.

The summer Olympic Games were held in Melbourne, Australia from Nov. 22 to Dec. 8 in 1956.

Before the last world war, Japan had many world-class swimmers. In the Berlin Olympics in 1932, Maehata won the gold medal in the 200m breaststroke. During the war, there were several world record holders. Unfortunately, Japan was prohibited from attending the London Olympics in 1948, but Furuhashi recorded faster times in the 400m and 1500m freestyle events of domestic competitions than those recorded in London. Japanese people were deeply disappointed by the country’s absence from the games. Furuhashi’s records were not recognised outside Japan, but in the U.S. National Swimming Championships held the following year, he won to become the record-holder. People hoped he would win in Helsinki in 1952. However, being past his prime at that time, as well as suffering a bout of sickness just before the Games, he could only manage 8th place in the 1500m freestyle.

Yamanaka came along and took his place, becoming one of Japan’s strongest medal hopes. He was always in the newspapers and even an 11-year-old boy often read about him.

As well as newspapers, his face appeared in magazines, journals, cartoons and even on stickers for children. There were also detailed explanations of his swimming skills and how he’d developed them, and there can’t have been anybody who didn’t know him at the time. At the Melbourne Olympic Games, his race was, of course, broadcasted live, and I listened to it clinging to the radio. Australia was too far from our country for the telecommunication technology at that time, so there was a lot of background noise and the sound was constantly fading in and out. It felt as if the sound was travelling over the sea, conjuring up images of southern islands and big waves. Yamanaka achieved impressive results, getting silver medals in both the 400 and 1500 meter freestyle. However, most people were slightly disappointed, because they felt that only a gold medal would have helped them to overcome the humiliation of the war . He set new records in both races in later competitions and again was a major Japanese hope in the Rome Olympic Games. Again he performed admirably and won silver medals in the 400m and 400m relay freestyle events. Several other Japanese athletes won medals in both Olympics, but I was so enamoured with Yamanaka that I do not remember their names.

And now my hero was sitting in front of me, it was natural that I could not contain my excitement.

He explained his proposal: having remained involved in the swimming business after retiring from the sport, his company had recently developed a new process to treat pool water and had been gaining a good reputation nationwide. Up to that time, conventional systems had used calcium hypochlorite, CaCl(ClO)・H2O, to treat pool water. However, as you probably know, when swimming in water treated in this way, your eyes soon become sore, which is due to this agent. They had developed an irritation-free water purifying system that circulated the water through a box containing ground shells, and the system had been well-received by swimmers. Firmly believing in the potential of the business, the venture company that produced the crushed shells for the system wanted to increase the price of their product. Yamanaka was insisting that my company should provide them keeping the price that we had decided on.

“You know, it’s the usual business practice to lower the price when the sales volume is expected to be high – a higher price just goes against common sense,” he insisted.

“Yes, it goes against commercial code,” I agreed. It reminded me of a similar episode: One of my colleagues was travelling in China as a member of a representative group from the trade association. They found some good souvenirs at a gift shop in a city, but the shop’s stock was only small and there weren’t enough for everybody. The next day, they visited the shop and found the same item at double the price. Though there might well be such shops in places around the world, the price being inversely proportional to the amount sold is usually considered the norm.

“So we would like to ask your company to produce the crashed shells for our system, ” he declared in a tone that seemed to suggest that he was expecting a positive response to his proposal. However, it’s usually thought of as correct protocol not to commit to a definite answer when a proposal is initially received, so on parting, I just said, “Thank you for your proposal. I fully understand and we will give you our decision after careful discussion among the related divisions.”

After the conversation, for some reason I was left feeling something was strange but could not put my finger on it. A person who had been in the newspapers so often was a huge celebrity for somebody who was born and had lived in the countryside for more than forty years. (Actually, my name did appear once in the local newspaper in a list of successful university candidates, and my sole TV appearance was when I happened to be in the background of a still shot from coverage of a local event.) At first, I put it down to being overawed in the presence of such a star but couldn’t shake the feeling that it was something else. When I saw him off, it suddenly hit me – he was less than 5.6 feet tall, about the same height as me. Only having seen his face or the top part of his body in newspaper photos, I’d always imagined that he was over 6 feet tall. His face was quite long, and I guess most people imagine good swimmers to be tall – maybe that was it. I must have been too excited to notice when we first met, and he was sitting down for most of the meeting. I couldn’t help smiling to myself at the confusion my long-held misunderstanding had caused.

The end

<<< Showing again the story presented in Youtube >>>

1. Photograph (1953)

Wakening up from his doze, the boy didn’t know where he was or what he had been doing, so he tried to remember by going back over the events of the day in his mind. It had been a rainy day. Upon leaving school, he had invited several friends to his house – “Let’s go back to my house and play.”

All of his friends were the sons of farmers and usually had no time to play after school due to their farming chores and having to take care of their younger siblings etc. Even when they had time to play, they rarely accepted an invitation to come to his house, because they had so many other wonderful places to play: the mountains, rivers, lakes and even their own big gardens.

This day, the rain kept the farmers from their work and set his friends free from their duties, so today, unusually, they accepted his offer. They might have been interested to see his house, the only non-farming house in the village, or maybe they just wanted to enjoy a feeling of freedom in a house without adult.

As he only had a few toys, they listened to records of pop songs and comic stories. Then they amused themselves searching out the various antiques and household items that his family had acquired when they were living in the city – things that the boys had never seen in the village. When they tired of this, they started to play hide-and-seek. The author is not sure whether the game is similar in the UK but in Japan, the person who will look for the others is first decided by playing ‘paper, stone and scissor’. While that person is counting up to ten, the others hide themselves somewhere. Then he has to find everybody, with the person being found first becoming the finder the next time.

Naturally, as this was his house, the boy knew all the best places to hide, and the place that he chose to secrete himself was indeed so well hidden that the other boys couldn’t find him. While he was waiting to be discovered, he fell sleep. Waking up, he couldn’t hear a sound, and then he realised the others had got fed up with looking for him and gone home.

He looked around. It was the first time he’d been in there since they’d moved to the house. Mice used to be common in houses in the country, and this space smelled of mouse pee. There were many things he was not familiar with, so, being alone until his family came home, he started to explore.

There was a big wooden box capable of containing a man, a chest of drawers, a big tin can four feet in diameter and four feet high, and many miscellaneous tools and small boxes. The big box was attracting his attention, so, removing the cobwebs, he opened it. He didn’t expect to find anything valuable in it, because he knew his family was not wealthy, and he’d often heard his mother complain about how they’d been defrauded out of the only family heirloom of any worth – a Japanese-style painting – by some villager.

After the war, most people in Japan suffered from a shortage of food due to the collapse of the nation’s economy. People could not live with the rations they received and staved off hunger by buying food on the black market. There was a report that a high-minded judge died of hunger after refusing to supplement his food allowance with illegally obtained food. Being in the countryside, the boy’s family did not face such great hardship. They left the specialised work of growing rice to the farmers in their community, but they grew all the vegetables they could, so they had quite a selection of farming tools.

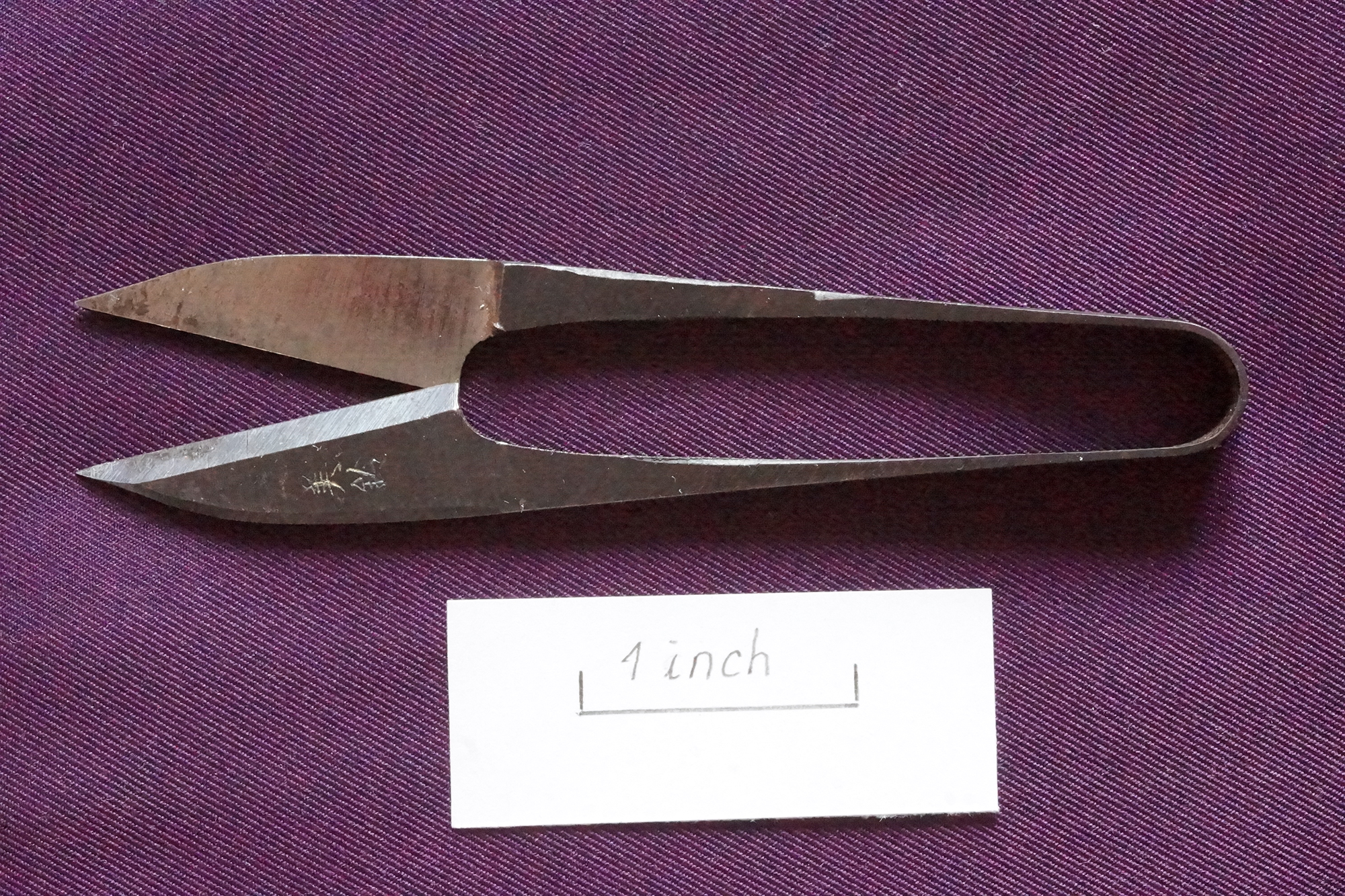

- Big Japanese scissors with a blade of about ten inches: Scissors in the UK (called European scissors in Japan) consist of two blades with finger holes, and things are cut by opening and shutting them with the fulcrum of the connecting screw. Japanese scissors are U-shaped, as shown in the following figure. These scissors are structurally suitable for delicate cutting like the needlework of Japanese clothes (Kimono). On the other hand, it is very difficult to cut hard and/or thick cloth. The boy had heard this before, so, not being tailors, he could not imagine why his family was in possession of such big a big pair. Afterwards, his mother told him that they were used for cutting wool. Her answer made him even more curious, because few sheep were raised in Japan at that time, and there were no sheep in his village. They undoubtedly would have been able to sell wool at a good price. However, to his knowledge, his family had never had sheep and even if they had, it was such a small farm that they surely only could have kept one.

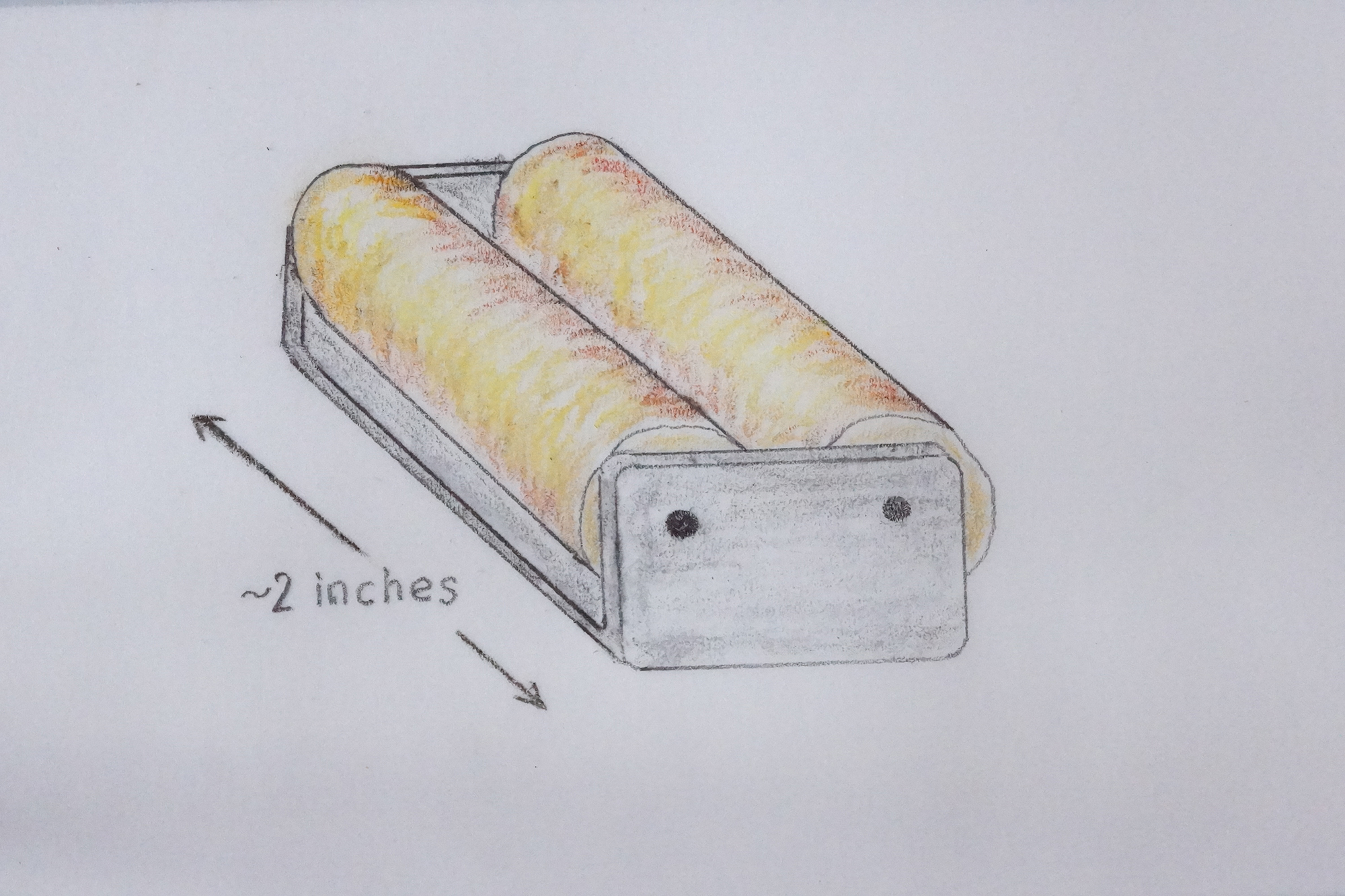

- Small aluminum frame with two round wooden bars : Two wooden bars with a diameter of about 0.4 inches fixed in an aluminum frame. They could rotate freely and one of them was movable, enabling control of the space between them. The boy could not think what this was used for, but he later found out it was a cigarette roller. This puzzled him. Cigarettes are made under license, so using the device to roll one’s own would have been illegal. He understood that there was a shortage of many things in the war, so maybe that’s why it was overlooked. Even so, he could not understand why anybody would want something that you couldn’t eat, such was the hardship of obtaining food. He inspected all the things he had never seen before one by one, but I’m afraid I don’t have the space to describe them all now.

+Photograph:

He opened the door of the book cabinet and noticed envelopes sticking out from between the pages of thick books. Many photos were in them. A good number of them were young ladies wearing Japanese or Korean clothes. There were many scenic pictures as well. Later, his father told him that he had taken many photos with the camera he’d been given for work when he was with the Japanese occupation government in Korea. The boy asked him why he took so many photos of young ladies. He answered, “It is an accepted way to capture an image of beauty with a camera. Some people were suspicious of my reasons for taking them but my motive was purely artistic.” The boy couldn’t entirely understand what his father was saying, but he remembered that Korean ladies were especially beautiful. Anyhow, the camera was German, a Zeiss Ikon. At the time, it was said to be as expensive as a house.

The last book he looked at was an album containing family photos. He turned the pages and became more and more depressed. In one photo, his parents and two sisters were well dressed and smiling in front of an array of appetizing dishes laid out on a table. Other photos also bore witness to the wealthiness of his family. The boy could not imagine such sumptuous living. As far back as he could remember, his family had been poor, and he’d only ever eaten plain food and always dressed in old clothes. He had hardly ever had his photo taken. The oldest one with him in it was from a group photo taken at his elementary school entrance ceremony. Though in no way could they have been considered rich, after his mother got the job as a teacher, their lives had improved and become more comfortable. The boy had never imagined that his family had known such prosperous times, and he felt quite alienated to realise it. Also, for no apparent reason, he was impressed by a picture of three teenage girls wearing beautiful kimonos.

2. Whisper of the Devil (1958)

Schools in Japan have two long annual holidays – one in summer and the other in winter, of which the length differs depending on the district. As the Japanese archipelago extends a great distance from north to south, the southern part has long summer holidays and short winter holidays, and vice versa in the north. The boy lived in a northern district with a long winter holiday, which resulted in him having a lot of homework.

Since early times, heating systems had been primitive and people shivered their way through the cold winters. City families had a wooden hearth as the main heater in the living room. It was a box three feet long, a foot wide and a foot high, which burnt charcoal and contained the ash. When using other rooms, they took a fire-bowl, which was a ceramic pot about a foot in diameter and contained the burning charcoal. Of course, these heaters didn’t keep people warm enough, so they had to put up with the cold, especially in the northern districts and plain areas. But for the people living in the northern part of Honshu island and mountain areas, the standard heating system was (and still is in some households even today) supplemented by using another heater – a kotatsu. This was like a table three feet square and a foot in height, covered by a quilt and with a ceramic box containing the burning charcoal and ash attached to the underside of the table. People got warm by sitting on the floor with the lower half of their body inside. When it was really cold, they used the fire-bowl as well, and even put on heavy winter outdoor clothes. The farmhouse had a big plain hearth (about five feet square) on the floor at the centre of the living room, and they kept warm and cooked burning wood from dead trees. In Hokkaido, even all the above-mentioned measures were inadequate, so western style stoves were used to heat up the whole house.

The boy’s family lived in the northern part of Honshu island and used a kotatsu. In the New Year holidays, his elder sister came visiting from the family she had married into, and the whole family – mother, two sisters and the boy – sat together around the kotatsu. (Their father wasn’t there, and they were so used to his absence that they never gave him a thought.) Outside the house, everything was frozen under a white blanket of snow, while inside, the sun shining through the window made it quite warm. The women were chatting listening to the traditional Japanese music that was part of a special New Year programme on the radio. He had intended to make a printing block for a woodcut print that was part of his winter holiday homework, but looking outside at the snow and listening to his family had put him in a lazy mood. He started patting his second eldest sister on her arm playfully. She was five years older than him and usually did not respond to his provocations. This time, however, she started patting him back, and their playful exchanges went on for some time. While playing with his sister, he remembered his homework and started fiddling about with the engraving chisel. He started to engrave a figure on the wooden plate but still kept up the messing about with his sister. Then, just as he was moving the chisel from his right hand to the left, she attempted to pat him, only to end up hitting the sharp end of the chisel. “Ouch”, she screamed. Blood dripped from her middle finger.

“What on earth did you do? You idiot.” His mother scolded him, hitting him on his head.

“Mom, you are wrong. It was her fault. I was watching them,” the oldest sister insisted.

“That might be the case but anyhow, we’d better take her to the hospital and get the cut looked at.” His mother had regained her composure a little.

After his mother and sisters had left, the boy snuggled in the warmth of the kotatsu and ruminated on what had just happened. He thought, ‘I was certainly tired of playing that game and was looking for a way to end it. If I’d said I’d had enough, this would have meant that she had won, so there was no way I was saying that. I remember thinking that while I was engraving, and then just when I shifted the chisel to my right hand in order to change the cutting direction, her hand got in the way.’ He thought it over again and again – ‘Umm, I suppose on some level I might have known she was going to put her hand there. Did I do it on purpose to end the game? Had the Devil put the idea into my mind? No, that can’t have been the case. I was not thinking that before the accident. But maybe I was and I just don’t want to remember.”

He went over it many times and ended up feeling really guilty.

3. A natural misunderstanding (1954)

It was twilight on a day in Autumn. The boy was waiting for his mother to come home in the living room with his sister. Many autumnal insects were singing together, blotting out the murmur of the stream behind their house. Japanese usually enjoy the sounds of insects, but they were so hungry that all they wanted to hear was the sound of their mother approaching their house. Presently, her footsteps could be heard from a little way off, and gradually they became louder. Somehow, the sound of her steps seemed to be different to usual. After changing her clothes, his mother started to cook the food that his sister had prepared, and he was laying the table. Suddenly, there was a loud sound from behind him. Turning round, he saw that his mother had fallen in a heap.

“Mom! Mom!” he cried out. His sister rushed in and started crying when she saw her mother just lying there.

“Mom! Mom!” they continued shouting. Their mother was out cold and just lay there snoring loudly. They had no idea what to do, so his sister ran to a nearby house to ask for help. He couldn’t do anything but cry kneeling down next to her.

“Mom! Mom! Mom!” he called out to her many times. After some time, her breathing became easier and the snoring decreased, and she gradually regained consciousness. In a faint voice, she started speaking : “I was trudging around somewhere in the dark, and then I came upon a field abloom with many beautiful flowers. Under the gentle sunshine, butterflies fluttered amongst the beautiful flowers. I was walking slowly, feeling like I was being led by someone. We walked through the flower garden and came to a big river, where a ferry was moored. Just when I was about to get onboard, I thought I could hear you calling me from far away. You seemed to be urging me not to get on the boat, and I couldn’t make up my mind whether to board or not. I put one foot on the boat and heard you calling clearly, “Mom, come back.” I stepped back on to the shore and woke up. I realised then that if I had gotten on the boat, I would have died. You saved my life!”

Please read the sequel of this story in the home page version.

The end